I dreamed long ago of a tiger wearing a dhoti (a white cloth wrapped around her pelvis), sitting in a cage of iron bars, with her body twisted completely in knots, legs forward and up, ankles behind head, sitting still and quiet in a yoga pose. She seemed accepting and friendly.

The dream was one of a series that gave me instructions, an assignment, and messages about how to find the doorway into my real life.

Since childhood, I had both an ambition to achieve and reckless ferocity. Over time, my inner tiger’s pursuits formed a strong network of habits I mistook for my identity. In a conversation about the weather, the tiger sought to win. On a contemplative walk with a friend, the tiger schemed underneath to be the wiser. In choices between thinking and listening, the tiger lay ready to leap out of my mouth with knowledge about this and experience about that.

Carl Jung wrote that people who want to become conscious need to go against their own nature. My dream said I could find peace and inner warmth by developing strength of character and flexibility – the pathways of yoga. If a wild tiger represents fiery desire and aggression, then a quiet, efficient furnace symbolizes friendly mastery of that nature. The path of getting there appears in the dream as the practice of yoga.

In yoga, restraint, containment and devotion propel incremental changes. These changes function like a serum for someone with amnesia. Who was that person who wreaked havoc in my life before? Who is this better person I’m discovering underneath layers of programming? Clarity bubbles up like springs of hope. I start to be moved by beauty, stirred by imagination, awakened to subtlety. The nuances of life whisper graces into silent spaces.

The dream showed that a tiger without pride and violence eclipses expectations of reality. A tiger in a cage in Dwi Pada Sirsasana overcomes her larger opponent (Iyengar, “Light on Yoga” 307). The yoga tiger courageously abstains from threatening others. She eats her own desire. She practices. The flames of the yoga tiger consume her anger on the inside. She wins contentment. Then the fire burns in her belly like a well-tamed furnace.

Photo by April Hayes, April Rain Photography

Habits that portray themselves as an identity stand in the way of identity. But this is like a Chinese finger puzzle: How can a false identity be identified by itself? If I see everything through the lens of a false identity then how can I see what’s false about it?

This is where dreams come in. Carl Jung recognized a type of dream that speaks from a deep layer of the psyche with understanding of the dreamer’s greatest potential and deepest character. Various Native American peoples called this type of dream a “big dream,” and Jung respectfully used this term as well. Often these dreams express urgency, intensity, profound beauty, grand stories, inscrutable or unusual imagery, or vivid colors.

Writing of his experiences with the Huron people in the 1600s, Paul Ragueneau wrote that “The Hurons believe that our soul has desires other than our conscious ones, which are both natural and hidden, made known to us through dreams, which are its language. When these desires are accomplished, the soul is satisfied” (Thwaites, ed., 33: 195).

Consider one of the earliest remembered dreams of Jung from when he was about four (Jung).

The vicarage stood quite alone near Laufen castle, and there was a big meadow stretching back from the sexton’s farm. In the dream, I was in this meadow. Suddenly I discovered a dark, rectangular, stone-lined hole in the ground. I had never seen it before. I ran forward curiously and peered down into it. Then I saw a stone stairway leading down. Hesitantly and fearfully, I descended.

At the bottom was a doorway with a round arch, closed off by a green curtain. It was a big heavy curtain of worked stuff like brocade, and it looked very sumptuous. Curious to see what might be hidden behind, I pushed it aside.

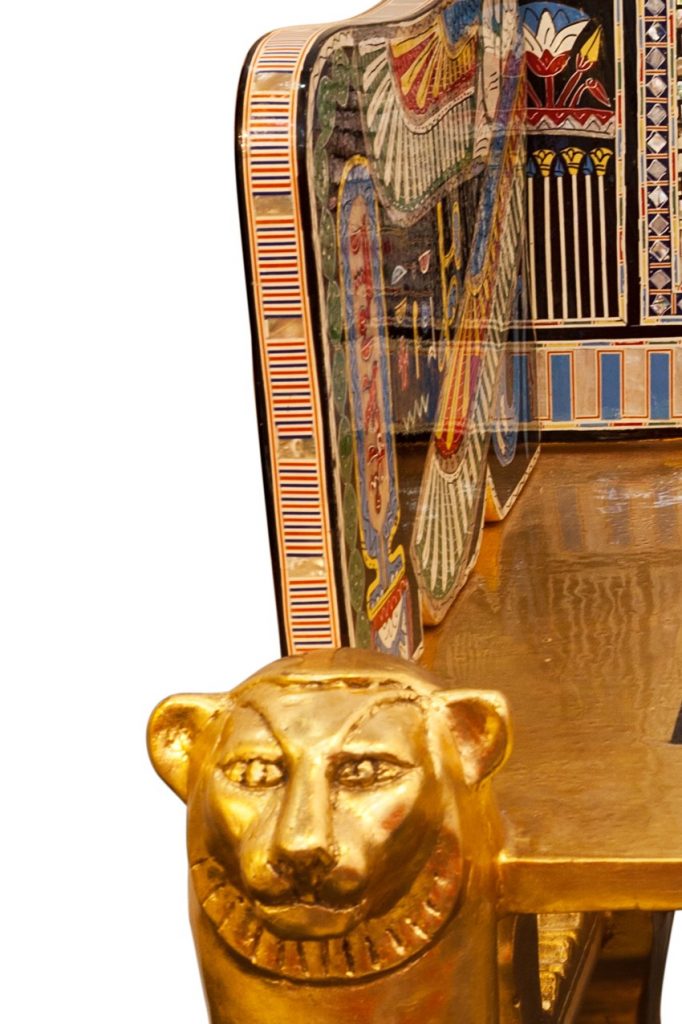

I saw before me in the dim light a rectangular chamber about thirty feet long. The ceiling was arched and of hewn stone. The floor was laid with flagstones, and in the center, a red carpet ran from the entrance to a low platform. On this stood a wonderfully rich golden throne. I am not certain, but perhaps a red cushion lay on its seat.

A detail from a modern copy of the Egyptian Golden Throne of King Tutankhamen

It was a magnificent throne, a real king’s throne in a fairy tale. Something was standing on it which I thought at first was a tree trunk twelve to fifteen feet high and about one and a half to two feet thick. It was a huge thing, reaching almost to the ceiling. But it was of a curious composition: it was made of skin and naked flesh, and on top there was something like a rounded head with no face and no hair. On the very top of the head was a single eye, gazing motionlessly upward.

It was fairly light in the room, although there were no windows and no apparent source of light. Above the head, however, was an aura of brightness. The thing did not move, yet I had the feeling that it might at any moment crawl off the throne like a worm and creep toward me.

I was paralyzed with terror. At that moment I heard from outside and above me my mother’s voice. She called out, “Yes, just look at him. That is the man-eater!” That intensified my terror still more, and I awoke sweating and scared to death.

Jung’s dream showed his future self as a creative conduit for modern understanding of the inner world. As this carrier of divine creative impulses on Earth, symbolized by the tree-like phallus, he was to look up and receive inspirations from the unconscious mind, no matter how unexpected or unearthly they seemed.

He could expect that his conventional internal voice of safety and security (the mother) would try to scare him away from his calling.

In times past, people of a well-led kingdom understood the king or queen as a divinely called and capable representative of God’s goodwill toward the people. They expected wisdom from the king’s or queen’s decisions, and this created well-being in the kingdom. Jung’s big dream showed that his greatest potential and deepest character was to discover and embody a creative voice that would bring revelations from the unconscious into the modern world, like a king that brings good fortune to others. That was the gift he brought, and at the same time, his sacred identity.

Though big dreams come at various stages in life, often the earliest remembered dreams from childhood are big dreams. Young children, often still very open to the unconscious mind, tend to feel their soul’s hopes and desires. They receive dreams with a minimum of censorship and tampering by their egos. These big dreams talk about the possibilities of life. They intimate the great benefit this particular person could bring to the world, the one-of-a-kind personality this person could become while working to complete the endeavor of this particular, never-to-be-repeated life. It’s written in the holy, ancient stars where the dream came from. Something astounding could happen if this person will choose boldly. A big dream tells about a big life.

In ancient Chinese culture, to receive “the mandate of heaven” means to become t’ien-tzu, the son of heaven (Miyuki18). In parallel terms, John’s Gospel in the Christian Bible shows the Pharisees horrified that Jesus calls himself “Son of God.” Jesus reminds them of the passage in Hebrew law in which God speaks to them, “I say you are gods.” (Alexander 205; Sanford 65). He seems to have wanted them to realize that he was living his mandate of heaven, and they were meant to also. The whole concept of yoga is based on living out a calling and gaining freedom from small-minded internal programming. “If dharma is the seed of yoga, kaivalya (emancipation) is its fruit.” (Iyengar, “Light on the Yoga Sutras” 4).

“When you are inspired by some great purpose, some extraordinary project, all your thoughts break their bonds; your mind transcends limitations; your consciousness expands in every direction; and you find yourself in a great, new and wonderful world.” — Patañjali

We’re born for two lives. The big life echoes inside from the time of early childhood. It’s the face before you were born. It may appear in pretend games, passionate interests, and in earliest-remembered dreams. It radiates behind the façade of a small life. It’s as if an eagle’s egg were dropped into a nest of border-patrol drones. After hatching, she tries to fit in and succeed. She patrols like a machine, following orders. If she’s lucky, she becomes forlorn, wanders around searching for what’s wrong with her life, and discovers the exquisite curves of her flight patterns.

In my experience, the how-to manual for leaving the small life is in a person’s dreams. Another dream of mine that gave such instructions was this:

I see a superstar basketball player – a tall African American man. I want to be like him. Then the dream shows a montage of his history – his long record of small successes that gradually make him skillful. Extreme perseverance in small victories. No overnight sensation. No rebellious drama.

Dismantling my small life requires one effort after another after another. The desire for grand achievement reflects a hunger for accomplishment of a soulful endeavor. This means gradually gaining skill, completing tasks, and winning points by relinquishing procrastination, discouragement, torpor and other programming – 2 points at a time.

Compared to living by trial-and-error, the inner path propels personal development at the speed of light. The demise of the small life fires the ignition of the big life. Each effort of dismantling the small life is like a spark that warms the engine of a Lambourgini. When the car comes alive, it may become clearer where to go. The dismantling of a small life gives rise to illumination. Illumination shines on the unseen world. Like a getaway vehicle in the inner world, the purposeful endeavor of a big life has the engine, the acceleration, the spark, and the fire to burn up the small life like burning up the streets.

Each of us is born with a thirst for certain experiences paired with a need to resolve inner problems. A life pulls as if magnetized toward learning that’s tailored to the person. Those experiences offer opportunities to master the inner jungle.

The more mastery there is, the less background static. Less static equals more clarity. More clarity brings the ability to recognize how and where the small life programming is operating. This recognition brings the great power to make choices that further pierce and dismantle the small life.

My experience with dreams tells me that each person has a priceless, matchless potential often revealed in early childhood. The uncovering and bringing into life of that potential is a process that reveals, solidifies, purifies, and clarifies the person’s most superior character. The desires of the big life burn up the desires of the small life.

Each of us is invited to deliver a boon from heaven; to play a role no one else can, in propelling personal and planetary evolution. It’s the Buddhist mandate, the Jewish law, the Christian call, the yogic bedrock.

By being born, each of us has been invited to uncover and bring to life a unique and sacred identity on Earth. Bringing that identity to life also means accomplishing a task for the sake of the greater good.

My deeper identity is like an ancient temple buried in layers of earth. If I dig out the temple, I excavate a remnant from a timeless place – from the realm of eternity rather than the dust of a hillside.

We are the carriers of immense value, like the Hebrews who carried the Arc of the Covenant. We are each entrusted with manifesting our sacred identity in this life. Archeologists dig for what lies in the past. We can dig for what belongs to the future.

Morning From Ashes

Before I’m born, my big dream

wanders the land pining for a big life.

I come down to Earth, make a mess

of my life, then sort out its component parts,

the dirt from poppy seeds, jewels

from poison berries. My big dream sweeps in

one night with news from the ancient stars

and a proposal for us to passionately unite

in an outrageous endeavor until death do us part.

That dream has no retirement plan.

My big life seeks me, hunts me, wants me,

recklessly careens toward reckoning,

burning the firebird of my selfish desires to ashes

with flame rising, wing sweeping

the sins of the fathers spent in creation

of the child who sings light into morning.

Works Cited

Alexander, Victor. Aramaic New Testament.CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013.

Iyengar, B.K.S.Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patañjali. Harper Collins Publishers, 1993.

Iyengar, B.K.S.Light on Yoga. Schocken Books Inc., 1976.

Jung, Carl. “The Man-Eater.” World Dream Bank, 1879, www.worlddreambank.org/M/MANEATER.HTM. Accessed May 20, 2019.

Sanford, John A. The Kingdom Within: The Inner Meaning of Jesus’ Sayings.Harper San Francisco, 1987.

Spiegelman, Marvin J. and Mokusen, Miyuki. Buddhism and Jungian Psychology. New Falcon Publications, 1994.

Thwaites, Reuben Gold, ed. Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791. Burrows Brothers, 1896-1901, 73 vols.